Sapphire: The SQL Slammer

The beginning

25 jan 2003, 7:11 AM :

MS SQL WORM IS DESTROYING INTERNET BLOCK PORT 1434!

Everyone running MS SQL Server, shut it the hell down!"

In that morning Michael was the first to report, and one of many to witness, the early moments of the malware that would later come to be known as "Sapphire" or the "SQL Slammer", a worm that exploited a buffer overflow vulnerability that was already publicly known at least a year prior and patched by Microsoft 6 months earlier. With a total size of a measly 376 bytes, the worm would fit a copy of itself entirely within a single UDP packet, and send itself to new random IP addresses on port 1434. Once downloaded into the memory of a vulnerable server, it would then exploit the buffer overflow vulnerability to repeat the process. Other than that, the worm included no payload, did nothing else, nor did it even ever save itself to the hard drive, meaning simply restarting the system was enough to clear an infection. Despite its small size and apparent lack of malicious intent, Sapphire's destructive ability is not to be underestimated.

The consequences

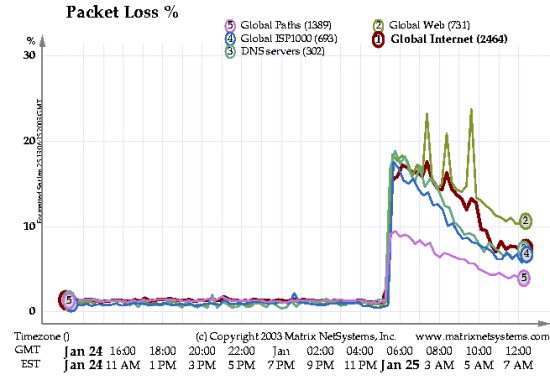

Within 10 minutes of the worm first being released to the wild, 90% of the vulnerable hosts on the internet (somewhere between 75,000 and 350,000 computers) were already infected by it. Because the packets containing Slammer were so small, many times the worm would receive priority over actual legitimate data being transmitted. There were so many servers spraying out these packets as fast as they could that there was basically no room for other actually useful internet traffic to go around. Even though all it took to purge the malware from your server was a simple restart, as soon as you were connected to the internet again, you would once again be receiving millions of copies of it every second. The only solution was to block port 1434 and download the software update from Microsoft which had already patched the vulnerability 6 months prior to Sapphire being deployed. But while the internet was overwhelmed by the worm, even the act of downloading became a challenge.

As if the worm spreading itself taking up most of the capacity of existing routers wasn't bad enough, there was also a secondary effect which worsened the slowdown the internet was experiencing. When a router crashed because of the overwhelming amount of traffic from the worm, its neighbors would notice it stopped responding, and update their routing tables to remove that router from the list of possible connections. They would then send that information to all other routers they knew, creating a propagating wave of table updates that slowed down the internet even more. And whenever a poor technician tried to restart a crashed router, it would be added back to the list in the same way, repeating the process and creating yet another wave of table updates, contributing to the massive DDOS attack the internet was inflicting upon itself at the time. Out of the world's 13 root DNS servers in 2003, 5 were entirely taken down, and another 5 were experiencing massive packet loss.

Damage report

During the morning of January 25th, the impact was so severe that most systems that relied on the internet around the world simply stopped working. For Microsoft, they couldn't even run their Windows XP activation servers anymore, nevermind the servers that distributed the patch that fixed the worm's exploit. Airlines had to use pen and paper to manage sales. ATMs became useless. Credit cards wouldn't complete transactions. The 911 network in the United States was no longer responding. The worm even found its way into an airtight network in a nuclear power plant in Ohio (by way of an employee's personal notebook), which thankfully was already shut down for maintenance. South Korean media claimed the whole country entirely lost access to the internet. All in all, the internet was plunged into chaos for days to come, though as news of blocking port 1434 spread and acessibility to the security update improved, it gradually faded away.

Estimates for damage by Cnet and Mi2g range around USD$900 million and $1.2 billion in the first 5 days of the worm, by means of direct damage and lost productivity.

Theories, Curiosities

The origins of the infamous SQL Slammer are still unknown to this day. Because it spread so incredibly fast, it's difficult to pinpoint the specific point of origin. And because the vulnerability it used was publicly known, anyone tech-savvy could have done it. Czech police accused Benny, a writer for a virus magazine of the time, of being responsible for the worm, although that would be uncharacteristic for members of the group since they never released any of their viruses into the wild. It is possible that someone else could have copied some code Benny was working on and released it into the wild, although none of the code he published matches the functionality of the Slammer.

Reverse engineering of the source code indicates that the worm might have actually been accidentally released; The prevailing theory is that a malware creator had an interest in creating a pseudo-random IP generation algorithm for spreading malware that integrated vulnerable computers into a botnet, and while testing it in an internal network, it leaked into the wild. Nevertheless, its true creator still remains anonymous.

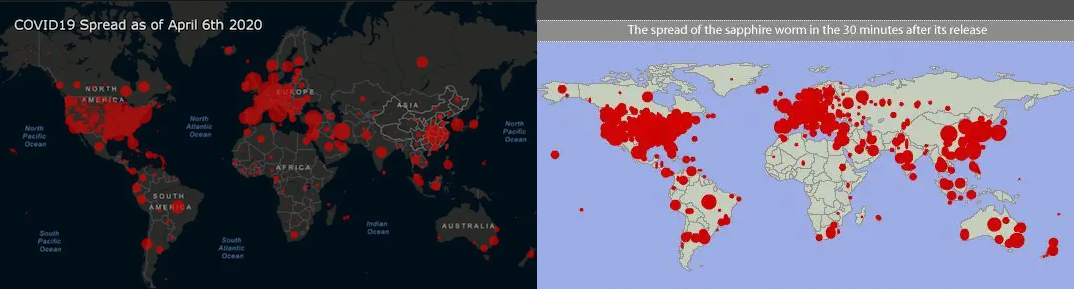

Since then, the spread of Sapphire has become a famous subject of study for many fields of science, including but not limited to infectology. Curiously enough, the pattern of infections during the early months of Covid-19 almost exactly matches that of the Sapphire worm. Check out these maps:

Eerily similar, huh? There's a lot alike between the way real diseases and computer malwares spread, which is a big part of why I'm so fascinated about the topic.

Closing Statement

Nowadays, the epidemic of the SQL Slammer is pretty much over. Mysteriously, it resurfaced again in 2016, being broadcast once more from servers worldwide, mostly in China and Mexico. Although this event did not last very long, and just as mysteriously it disappeared once again. Port 1434 has been cast into the trash bin of global networking, being blocked by default in pretty much every router or server software you can get nowadays.

There's probably still a few computers out there that remain unpatched since that fated day in 2003, left forgotten in a dusty server room, screaming the Slammer into the void until the end of time, hopelessly trying to find a host who will accept its message.

actually probably not, but it's kind of poetic to think about, isn't it?

If you've read this far, you're awesome! I know the information I'm bringing isn't exactly a groundbreaking new discovery or an in-depth technical analysis, but I just wanted to write about a topic of interest of mine, and I had fun doing it. Thank you!