CIH - 'Spacefiller' or 'Chernobyl'

The day is April 26th, 1999.

It is a monday like any other.

You get home from a tiring day at work. It's time to unwind and play some video games on your brand new PC. Maybe you'll play Diablo 2, maybe Heroes of Might and Magic. Maybe even some Duke Nukem 3D. Well, you'll find out in a second. First things first, you sit down at your desk, get comfortable, power on your PC... But it doesn't start.

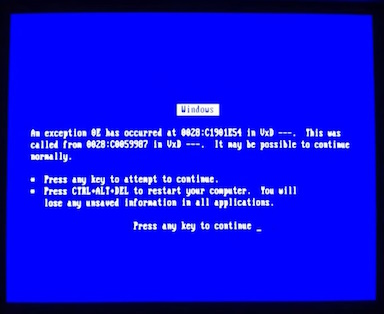

Instead, you get a blue screen. It reads:

"An exception has occurred (...) It may be possible to continue normally.

Press CTRL+ALT+DEL to restart your computer."

Press CTRL+ALT+DEL to restart your computer."

You try restarting your computer as instructed, and now you don't even get a blue screen anymore. In fact, the entire computer seems unresponsive. Pressing the power button doesn't even do anything. Baffled, you take the machine to your local technician, who tells you you've been a victim of the "Chernobyl" virus. He says your computer has been entirely destroyed, and might make a good doorstop now.

How did this happen? Your anti-virus program had never said anything about an infection. In fact, the computer was basically new!

The Infection

Well, the CIH virus - also known as "Chernobyl" due to it's activation date - used quite a clever method to avoid detection by anti-malware programs. Many such programs at the time relied on a file size check to tell if a file had been infected: Most viruses simply appended their code to the end of the file they wanted to infect, and by comparing file sizes before and after a program was run, it was possible to tell if something had infected it or not. CIH was only 1KB large - Small, but not small enough to avoid that method of detection if it were to append itself directly to the end of a file. Instead, CIH checked for small gaps in the portable executable files it targeted, and if it found enough of them, it would split itself into a bunch of tiny chunks and generate a small program for rebuilding the chunks together. This behavior earned the virus its other nickname, "Spacefiller". By inserting itself into these gaps, it could infect a file without changing the total file size or adding anything to the end of the file, making it much harder to detect by the anti-viruses of the time. Once your system was infected, the virus would do nothing and remain dormant - until April 26th.

In fact, it was so hard to detect, that not even large corporations were aware that they had it in their systems. Initially, CIH began spreading in piracy groups in 1998, including pirated distrubutions of Windows 98. However, as the virus continued to silently spread with no apparent payload, it eventually reached legitimate distribution sources. Origin was distributing infected copies of their 'Wing Commander game' through their website, Yamaha uploaded an infected firmware update for their CD drives, Activision's demo for 'SiN' was infected, IBM sold brand new Aptiva PCs that were already infected with CIH just a month before the activation date. Supposedly, an european PC gaming magazine shipped with a cover CD that was knowingly infected - and included a warning to disinfect your pc after using it. if you have an image of this magazine, please send it to me!

By the time the payload would activate for the first time, it is estimated somewhere between half a million and one million computers worldwide were infected.

The payload

The reason CIH got so famous despite not being as widespread as other worms of the era was its incredibly destructive payload, worthy of being named after a nulear incident. On april 26th - the anniversary of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster - CIH would activate an incredibly dangerous dual payload. First, it would attempt to overwrite the entire hard-drive with a sequence of 0's, beginning at the partition table. It went as far as it could before the system crashed. This left the computer unable to boot, since without partition data the disk could no longer be read, and operating system data became inacessible. The data that was overwritten was just unrecoverable - while the rest would require professional work done to see how much could be recovered. This alone was incredibly destructive, but CIH doesn't stop there.

After destroying your file system, CIH has its next target in sight - your BIOS chip, in an attempt to cause physical damage to your computer. This didn't work on every system, but if the virus hadn't already destroyed itself to a point of non-functionality during the first payload, and your BIOS was one it could write to, it would be overwritten with junk. This effectively killed your hardware and rendered your computer useless. While technically replacing the damaged BIOS chip was a possible fix, back then it was so expensive you might aswell just get a new motherboard. And flashing a new BIOS into the existing corrupted chip was even more expensive. If this part of the payload worked, that's it - goodbye, computer.

Damage report

Between its initial deployment in 1998 and the first activation in april 1999, CIH had infected around a million computers worldwide. However, it continued to spread after the first activation - finding a total of 60 million or so hosts worldwide, according to an estimate by taiwanese tech newsletter iThome, who also estimated global losses of around $1 billion Taiwanese Dollars ($35 million USD) due to the virus. Korean media claimed $250 million USD worth of damages in the country alone. However, it is hard to make an estimate of how much damage really was caused by CIH - people feared it so much that when a computer would break down due to other reasons, they would attribute it to this virus anyways, and technicians would happily report that the computer had indeed been destroyed by Chernobyl so that they could sell expensive services for repairs and data restoration instead of other, cheaper jobs.

Variants of CIH continued spreading until 2002 with slight differences, including other activation dates, different signatures, and one that famously appended itself to an email promising spicy pictures of singer Jennifer Lopez if the recipient were to open the embedded file, an early example of social engineering inspired by the "ILOVEYOU" worm.

Origins, Consequences

CIH was created by Chen Ing-Hau, who left his initials in a string in the code, which gave name to the worm. The activation date, April 26th, is actually Chen's birthday, and is not a reference to Chernobyl, though some sources say it might also be the date that the virus was initially released to the wild, and it was simply programmed to activate exactly 1 year after that. Chen said that he made the virus in order to prove antivirus programs who claimed invincibility against infections wrong, and that classmates had leaked it without his knowledge. He apologized for creating it, and worked to create and release a removal tool for his own malware.

Chen was never prosecuted, since noone attempted to sue him for the malware in court, and Taiwan did not have laws that classified Chen's actions as a crime. However, as a consequence of this a "Chapter on Obstruction of Computer Use" was added to Taiwan's criminal code.

He went on to become a senior engineer at Gigabyte Industries, and we probably have him and his Chernobyl worm to partially thank for computers with multiple BIOSes and easy flashing systems becoming the norm nowadays.

Personal thoughts, Closing statement

This worm has always been a source of interest to me. Not only due to it's destructive potential, which makes it a very scary - and therefore very fascinating - worm, but also because of the way it infects files. Fitting itself into gaps in the code to go undetected is a clever trick, but more than that, it's a step towards computer viruses that are more like their real counterparts. Some viruses that came after it used something called a metamorphic engine - which in combination with the splitting method, also randomly altered the code every time it spread.

While these metamorphic viruses aren't evolving in terms of functionality, they continue to change to avoid detection by antimalware scans that rely on databases of known viruses - much like real viruses continue to change every year to avoid detection by your immune system. And that was in 2001! Nowadays, we have viruses that change in much more advanced ways - though I'd like to learn more about them myself before I write a blogpost about them.

Thank you for reading! - Ayim